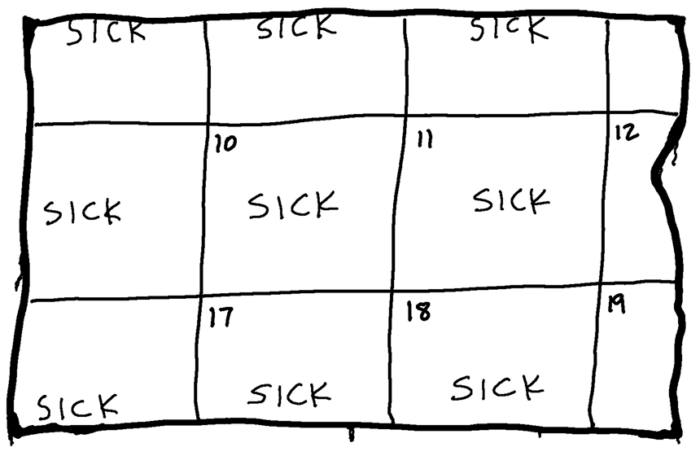

It’s been about a month since my last post and, quite honestly, it feels like longer. Ages seemed to have passed. A whole era. That’s probably because I came down with the worst cold I’ve had in years and have been both very busy and falling behind at work.

The worst part of this cold hasn’t been the coughing or the runny nose. It’s been the brain fog. I don’t know what the hell has been going on with viruses these days, but I feel like I’ve dropped about 20 IQ points. I don’t think I’m alone in this, either. I hear so many anecdotes about people needing weeks and weeks to feel mentally “normal” after they catch the bugs that have been going around.

Anywho. It hasn’t been fun. Such is the life of a teacher.

It’s Wednesday of spring break, and the weather is going haywire. Yesterday was 70 degrees and sunny. Today there’s a blizzard. I expect we’ll lose power at any moment, as is happening all over this part of Nebraska. Soon I will have to shovel.

I finished Mumbo Jumbo, which I didn’t like. It’s nothing to do with the book. I’m afraid I just read too much of it while my brain was melting due to fever. It doesn’t help that the book is awfully non-traditional in its structure, and the prose is by no means easy to parse. Even if I was at 100% brain function, I doubt I would have fully digested it.

They always say that authors have a specific person in mind whenever they write something — a person to whom the story is targeted, whether it be conscious or unconscious. (Freud, it is likely, really wanted to show his mom how smart he was.) This book, Mumbo Jumbo, is a book whose target (if they exist) utterly baffles me. Who is Ishmael Reed trying to speak to? Were there readers out there looking for him? Because I simply cannot picture anyone out there thinking, “This. This is what I’ve been waiting for.”

Which is fine. You don’t have to “get” every book that you read. Mumbo Jumbo, from what I can gather, was an experiment with form and the incorporation of African mysticism into some kind of noir mystery and written before I was born. I can snap my fingers to it the way I might snap along with a complicated Jazz record, but, ultimately, I’m a rock and roll guy. I could spend months with Mumbo Jumbo and it’d likely never click.

As Primus (who sucks) always says, “They Can’t All be Zingers.”

Today, in order to give my brain a much needed break, I’m going to read Frankenstein by Mary “Torso Face” Shelley.

I don’t know who did that painting, but it comes across as Gollum doing a Downton Abbey cosplay.

I’ve read Frankenstein about a dozen times, the most notable of which was when I moved to Seoul in 2014 and had to spend several hours at the Immigration Office waiting to get my visa stamped. It was one of the only times in my life when I sat down in a chair and read an entire book without moving, save to go to the bathroom or get a drink of water. (Shout out to the immigration office for making me wait several hours! Couldn’t have done it without you, fellas.) Frankenstein turned what might have been a trip to bureaucratic purgatory into a relatively pleasant afternoon.

It’s a skill I’d like to cultivate: Not just sitting and reading, but sitting and not consuming digital media for extended periods of time. Is it ironic that I’m writing this on a blog most people will read on their phones? Maybe. But my half-dozen regular readers appreciate irony.

These days, however, the goal of trying to avoid digital media seems more and more like starting a diet when you’re on a tour Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

…and we just lost power. Not for a long time, but long enough to cause my computer to shut down. So, I’m going to wrap this up before we lose it completely.

Stay safe out there.