For weeks now, I’ve been struggling to figure out a way to write about Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” #462 on the list of 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die. It’s gotten to the point that I’ve started reading books on literary theory to get inspiration. Most books on the subject are awfully dry and filled with the sort of academic jargon English departments are notorious for. 10-dollar words like “philology” and “hermeneutics.”

The issue isn’t that the book is hard to understand. Sure, the dialogue is written in dialect, but it’s not difficult for the average reader to comprehend. And the issue isn’t that the subject matter is inherently depressing, even though you do feel somewhat drained as you flip through the pages. A lot of bad things happen, and it can be difficult to read such a novel when we live in a world with so many bad things happening.

That isn’t the problem with my blogging about the book, though.

The problem is something usual, something that I experience with a lot of the books I read that are on this list: This book absolutely isn’t written for me. As a straight, white, American male, I am about as far from the “target audience” for “Their Eyes Were Watching God” as you can possibly get.

I feel like I’m bogged down by thinking of this blog as a “book review” blog, which is not what I want it to be.

I don’t want to give books five-star ratings. I don’t want to sell you on a story. I don’t even really want to give plot synopses, to be honest, although it’s hard to think of a way around it. What I want to do is have a chronicle of my journey (if you want to call it that) toward reading these 1,000 books. Something I can look back on in seven years’ time and think, “Oh, that was right around when the election happened and the whole world went to shit. My how time flies.“

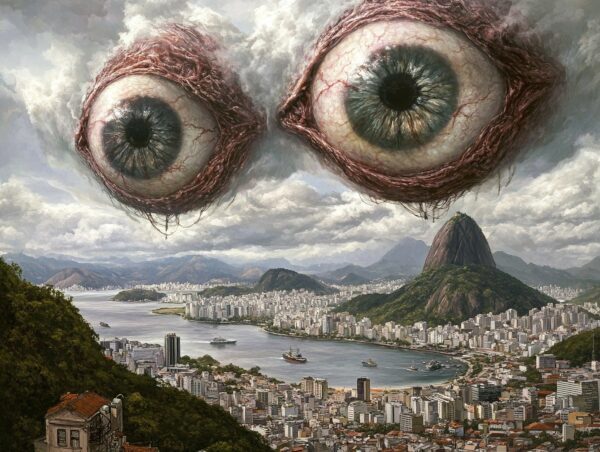

The whole thing is steeped in nostalgia. Nostalgia for a time when blogs were popular, when the internet wasn’t an ad-riddled, subscription-based nightmare of trackers and trolls and propaganda. Nostalgia for when we didn’t refer to this sort of thing as “content.” Nostalgia for when the internet was populated by people and you had a sense of community.

It seems as if we’re intent on killing that version of the internet. More’s the pity.

Anywho.

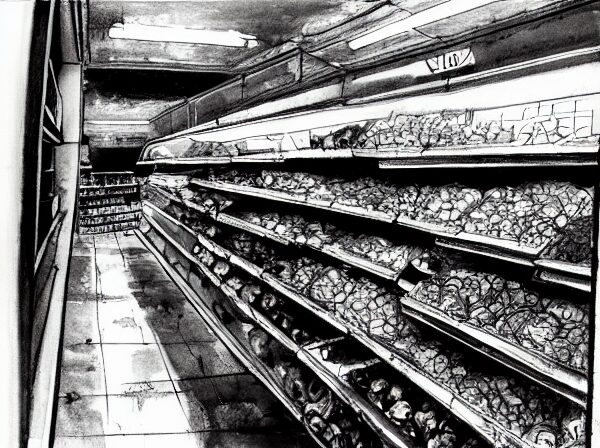

Zora Neale Hurston died in poverty after being nearly forgotten by the literary community. She had become popular during the Harlem Renaissance, but many people thought her work focused on the wrong topics — she tried to capture the everyday lives of black Americans rather than writing about social justice and the struggle for equality, which, naturally, were prominent topics in African American literature.

This is a simplification, of course, but sometimes books go against what are considered “modern trends” and fall out of public consciousness. This was the case for Hurston and many other “Harlem Renaissance” artists.

After Hurston died, scholars like Alice Walker “rediscovered” her writing and realized its uniqueness and importance. Suddenly, Hurston’s work was like a diamond that had been found in the garden, and Hurston has since become somewhat of an American staple — she is still taught in many U.S. classrooms, including my own.

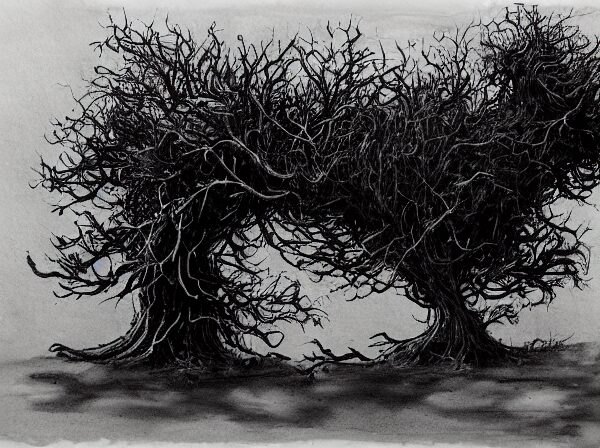

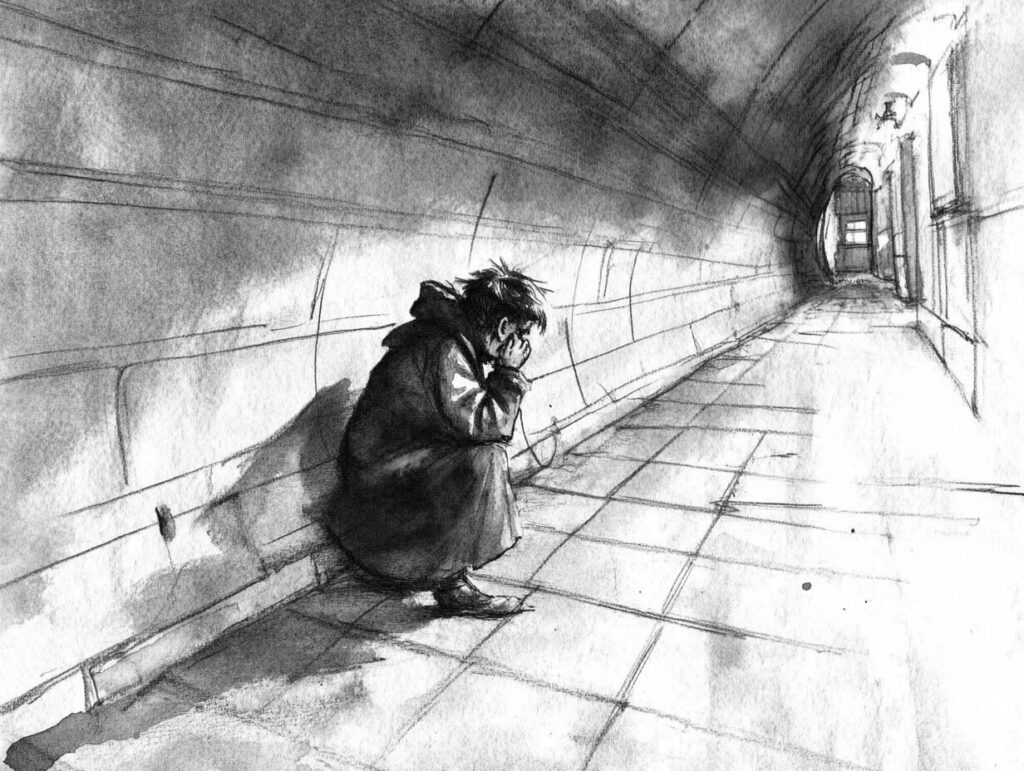

I often think about what it’d be like to be forgotten in that way. It isn’t quite the same, but recently I’ve been wishing I could experience it. I’m not saying I’d like to disappear, but I’ve been having this desire to…hibernate, if that makes any sense. I’d like to experience what it’s like to crawl into a cave, cover myself with leaves, and sleep for three to six months.

In fact, I have been sleeping a lot more than I usually do. When I get home from school, the first thing I do is crawl under the covers for a quick nap. After dinner, I also go to bed relatively early, often sleeping for 9-10 hours.

Is it seasonal depression? Maybe. Nights are getting longer, and the weather has finally turned into the bitter cold that’ll be tapping at our windows around until March. Ultimately, though, I think I’m just craving the feeling of sanctuary you get when you crawl into a warm bed in winter. The coziness, the safety. Much like I imagine a hibernating bear feels when her nature tells her it’s time to go into her cave. No expectations, no responsibilities, just me and my earthen hovel and my leafy blanket.

It’s interesting to consider the impact of a book upon someone who isn’t the book’s target demographic. I said earlier that “Their Eyes Were Watching God” wasn’t “for me,” but that thought is slightly more complicated than it seems on the surface. Whatever literary theory you subscribe to (which may be no theory at all, and God bless you), it’s difficult to read a book if you can’t put yourself into it. There have to be characters, themes, settings, plot points, whatever that resonate with you. Or, at least, that’s the way our modern education system has trained us to approach literature. Right or wrong, we read books and ask ourselves, “How does this make you feel?”

In the case of Zora Neale Hurston, I can recognize that there are elements in the novel that readers might identify with, but they just don’t hit me the way I think they’re supposed to. I don’t know any people who are like these characters, I’ve never had these sorts of marital issues, and I’ve never been to Florida.

I would probably say that it’s a “difficult” book for these reasons, but there are others. There’s a lot of dialect in Their Eyes. It’s enough that you often get the impression that you’re reading two separate books.

“Two things everybody’s got tuh do fuh theyselves. They got tuh go tuh God, and they got tuh find out about livin’ fuh theyselves.”

The prose itself is not written in this voice, but whenever we hear a character talk, that’s what it looks like. It made the novel an interesting and…er, novel experience, constantly switching between standard prose and prose in dialect, and there are many people in American society who use a variety of voices when they speak. Depending on the context, people can often have what you might call “dual personalities.”

Some of my students are prime examples. To hear them speak in the hallways is one thing, but the way they talk inside the classroom makes them come off as entirely different people. Are teenagers everywhere like this? Probably, to some extent. Teenagers all over the world act one way with their peers and another way around adults.

That, I suppose, is something we all can identify with. While all of us don’t have modes of speaking with such dramatic and noticeable differences, there are times when all of us feel like we are someone we’re not.

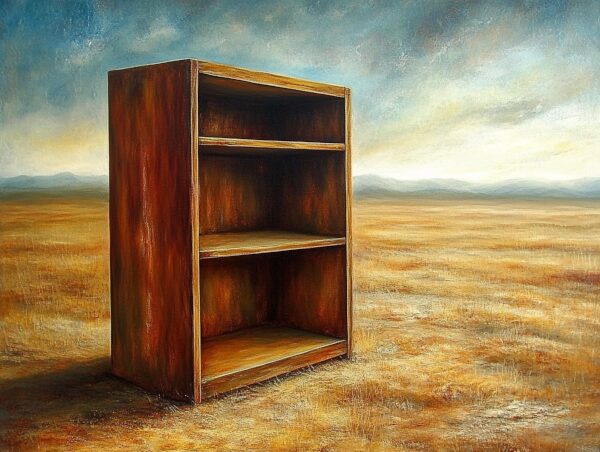

In my case, I often feel like I’m pretending to be a “good teacher.” I’m not sure if I even want to be what I’d call a “good teacher.” I’m a competent teacher — don’t get me wrong — but the line between “competent” and “good” is one that, in my own mind, I’m not sure I can cross. “Competent” teachers have to do a lot, but “good” teachers take on extra. Often times, they take on more than is healthy.

There are teachers at my school who are there 11 or 12 hours a day, teaching regular classes and then doing sports or activities after. They work on weekends, organize field trips, do fundraisers, and generally throw everything they’ve got into the teaching profession. I do care about my students, and I do everything I can to make my classes engaging and useful, but when that final bell rings, I want to go home and do other things. I want to have a life outside the building.

When I first became a teacher, things were different. I wanted a career I could throw myself into with every element of my being. I wanted to be like one of the characters on The West Wing, a kind-of Sam Seaborn who sleeps, eats, and breathes his work. The problem with shows like that is the fallacy that there are intelligent and moral people in charge of things. In reality, there are no whiz-kid doctors who’ll stay up all night to diagnose your medical condition, there are no tough-as-nails police detectives working overtime to catch the guy who broke into your house, and there certainly are no brilliant political officers who are trying to make the world a better place.

I know it’s putting awfully high expectations on myself when I say that I need to work 60-hour weeks in order to be “good” at my job. One thing that you learn if you study mindfulness or Eastern philosophies is that a person should be okay with being “okay.” You don’t need to be brilliant — it’s enough just to exist.

That’s just a tough pill to swallow when you live in a country filled with bozos who brag about how little sleep they’re getting or how much overtime they’re putting in. As if it’s some kind of badge of honor to work yourself to the bone for a system that couldn’t give less of a shit about you.

Last night, a freezing rain fell that covered the whole city in a layer of ice. Sarah and I went out to get some drive-thru chicken and quickly realized that we wouldn’t be able to get out of our neighborhood — there was no way to drive up even the slightest hill. We saw cars hopping curbs, cars that were stuck at intersections unable to move forward or backward, people who’d gone out for a walk and were slipping helplessly down the sidewalks.

Some nights you’re just stuck. Nature will always remind you of that fact.