English teachers are ready at a moment’s notice to not only explain aspects of literature, but to defend and justify literature to people who think it needs defending and justification. These are people we lovingly refer to as “idiots” — the vocal majority who have only ever picked up a novel when forced and, for whatever reason, feel no qualms when boasting about that fact.

Students gripe. It’s part of being young and not liking it when people tell you what to do, so you’ve got to be ready to talk back to them. Recently, when my students have gone off on a tangent somewhat parallel to “Why bother to read books?” which happens at least once a semester, I’ve told them this: “Books are the only media left that isn’t trying to sell you something.” Ads are everywhere — books are one of the only safe spaces left. While that’s more than enough reason for me to go to bookstores more frequently than I ought to, some bull-headed students require a little extra:

“Books allow you to glimpse into other lives and other times. This, in turn, increases your understanding of other people and your capability for empathy. Understanding and empathy are the things that make our world better.”

Welcome to Flatland: The Least Romantic of Dimensions

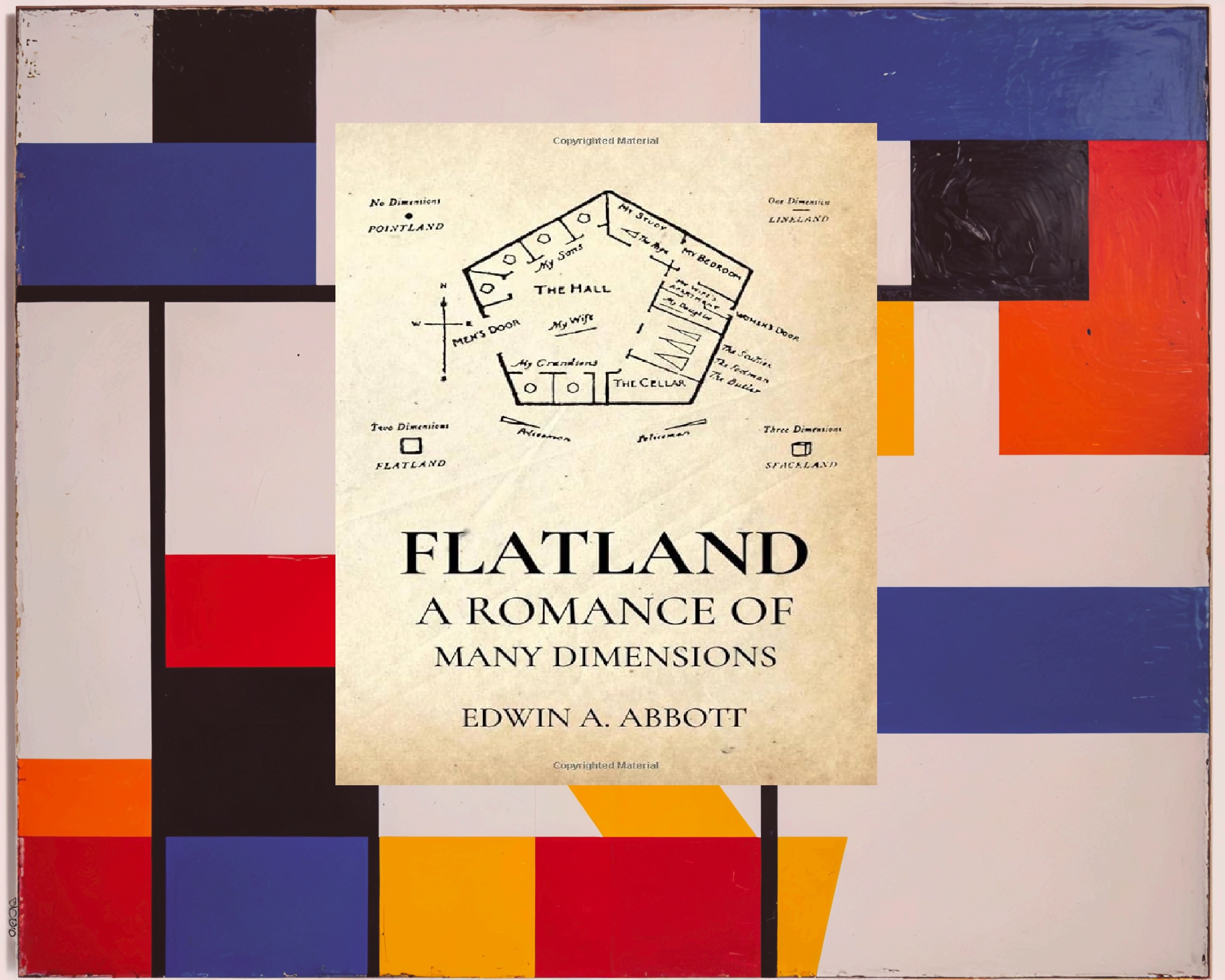

“Flatland: A Romance in Many Dimensions” by Edwin Abbott Abbott is one of those old science fiction books that hits you over the head with this idea. The book, pseudonymously written by one “A. Square” tells the story a … square (oh, I see what he did there) that lives in a 2-dimensional universe — their world has length and width but no height, so every creature and object is essentially flat. But more flat than we can even understand. To them, height just doesn’t exist.

The square explains a bit about the nature of his world, which turns out to be a satirical take on (mostly) British society and its rigid class hierarchy, before meeting a sphere (gasp!) and being brought into the world of 3 dimensions. Upon his return, Mr. A. Square is unable to convince any of his fellow Flatlanders that this 3rd dimension actually exists and is eventually jailed for his heretical ramblings.

It’s a short book (a novella, really) that doesn’t require much of a time commitment, and Mr. Abbott Abbott does a fine enough job of incorporating some exciting trigonometry, but I think the hook of this story is that There Are Things Out There That You Will Never Understand.

Wouldn’t You Like To Know

The same way that Mr. A. Square is utterly confounded by the appearance of a sphere in his 2-dimensional universe, so too would we be confounded if we were to encounter a being from the 4th dimension here in our 3-dimensional universe. It’s like trying to imagine what’s inside a black hole; our brains simply can’t comprehend it.

If we did encounter such a creature, we might mistake its voice for a voice in our own heads — they might be able to speak directly inside of us.

We would only ever see a 3-dimensional cross-section of it; we couldn’t ever witness it in its entirety. Meaning we’d probably get to see its 4-dimensional kidneys.

It would seemingly be able to pop in and out of existence.

No, It Wasn’t Carl Sagan’s Idea

My first exposure to Flatland came from the Cosmos TV series starring Carl Sagan, which rather brazenly recounts parts of the plot of Flatland and presents the concept in an easy-to-swallow way — it’s a lot more practical to discuss a 2-dimensional world if you have visual aids:

By understanding a 2-dimensional creature’s response to a 3-dimensional creature, we can extrapolate what it might be for we 3-dimensional beings to encounter a 4-dimensional being. At least sort of.

I think, more importantly, that it encourages us to come to terms with things that are beyond our comprehension. I don’t know where most people fall when it comes to solipsism — the philosophy that the self is all we can ever know — but I do recognize that it’s nearly impossible to fully understand another human being. We’re all a mess of memories and trauma and neurosis; guessing why anybody does anything can often seem like it’s beyond the wisdom of salmon.

I certainly don’t understand everybody. In a country as politically divided as the United States, it’s easy to look at other people and think, “Jesus Christ, what in the hell are they thinking?” My neighbor with a Trump flag on his F350 might not look like a 2-dimensional creature on the surface, but my understanding of him is much the same. He spends all his time moving back and forth in predictable patterns whilst ignoring what the rest of us see as obvious — all while keeping a weathered eye out for foreigners and grinding his teeth at property taxes.

How Many Dimensions Are There, Really?

It stands to reason that if a being from a 2-dimensional reality can become aware of a 3-dimensional reality, and if we can sort of imagine a 4-dimensional reality, then there could be more dimensions. But how many are there? Oh, where is Neil Degrasse Tyson when you need him? Probably tweeting about how unrealistic Alien: Romulus is.

Anyway: String Theory suggests that there could be 11 dimensions in our universe — 10 spatial dimensions and one dimension of time. If you think it hurts your brain to imagine the 4th dimension, just try to imagine what sort of wackiness is going on in the 10th. (So many Trump flags!) All I can tell you is that string theorists predict these dimensions are all around us but too small for us to interact with.

Unable to grasp such scientific mumbo-jumbo? Try drugs. I hear they help.

Who Was Edwin “Don’t Make Me Repeat Myself” Abbott Abbott?

Born in London at the start of the 19th century, Edwin Abbott Abbott became an educator at a young age after realizing how much he hated kids and desperately wanted to explain math to them. He was a homely fellow with a penchant for weak chins and was probably the sort of teacher that talked really quietly and then got mad when you couldn’t hear him from the back. “Maybe if you put your phone away my instructions would have been clearer, Beatrice.”

He wrote several books, but Flatland was easily his most notable.

Also notable: The word “Abbott” appears twice in his name because his parents were cousins. (Only partially joking.)

While Flatland may be seen as science fiction, many people call it “Mathematical Fiction.” It’s hard to imagine why that particular genre never really took off, but authors like Neal Stephenson are still miffed about it.

Final Results

Given its relatively short length, I’d say Flatland is worth your time. You won’t be dazzled by the prose, and the plot is just as cohesive as Gulliver’s Travels (that is to say: mostly incoherent), but it’s an fun thought experiment and there really is some interesting math-related stuff. I particularly like the explanation of how fog makes it easier to discern who is who in Flatland.

It almost makes up for the casual sexism and xenophobia!

If you’re interested in what encountering creatures from other dimensions might actually be like, there are a few modern authors who are doing some good work in that area: “Superposition” by David Walton is about alien intelligence developing in quantum randomness, and the Southern Reach Trilogy (of which “Annihilation” is the first book) lives and breathes the confusion one would feel while encountering alien, extra-dimensional life.

The Remembrance of Earth’s Past is another great series that deals directly with extra dimensions. Mild spoilers: Dimensions are weaponized by ultra-intelligent aliens. Don’t like your 3D neighbors? Collapse them into 2D. Boom! Now your neighbors have literally been flattened.