Note: This is based on the translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

By the end of “Notes From Underground” by Fyodor Dostoevsky, #285 on the list of Books to Read Before You Die, I’d gone from thinking, “This book is an absolute waste of time,” to thinking it really was essential reading. There were also lyrics to a Tool song going around and around in my head. The lyrics go like this:

Disembodied voices deepen my

Suspicious tendencies

Conversations we’ve never had,

Imagined interplay…

It took a while to get into, but by the time I reached the end of this novella penned by the guy who wrote books notorious for being some of the longest books ever, I had a pretty clear understanding of where Dostoevsky was going — it’s a character study of a man who takes a natural tendency to an absolute extreme, resulting in his self-isolation.

Existentially Speaking

Fyodor Dostoevsky led a difficult life. That sounds like I’m about to write a floppy research report on the guy, but it’d honestly take too long to get into all of it — people write books about the subject. Still, it’s good to know some basics:

Born into a somewhat wealthy family in Moscow in 1821, Dostoevsky was exposed to literature at an early age and worked as a translator before joining literary circles and beginning to publish his own work. His association with those same literary circles resulted in his being exiled to Siberia and then being forced into military service.

If all of that sounds miserable, you’re right, and the difficulties he faced no doubt contributed to his particular style of writing, which would charitably be called “depressing” and accurately referred to as “essentially Russian.“

“Notes From Underground” was published in 1864 and is widely considered to be one of the first examples of existentialist literature.

Existentialists look at the world through the lens of the individual and his search for meaning in a world that is often cruel and absurd. Other popular existentialists include Sartre, Camus, and Kafka — three people who, if they were playing a round of golf together, wouldn’t finish the first hole because they’d be too busy arguing about why they had to use clubs.

The way I think about it is this: You can’t spend years and years in Siberian exile without wondering if there’s a purpose to all this. Dostoevsky wanted to explore man’s search for meaning in his writing, which meant forgoing certain tropes you might find in earlier literature — heroes, plot, catharsis — and creating works that delved (too?) deeply into characters and their relationships.

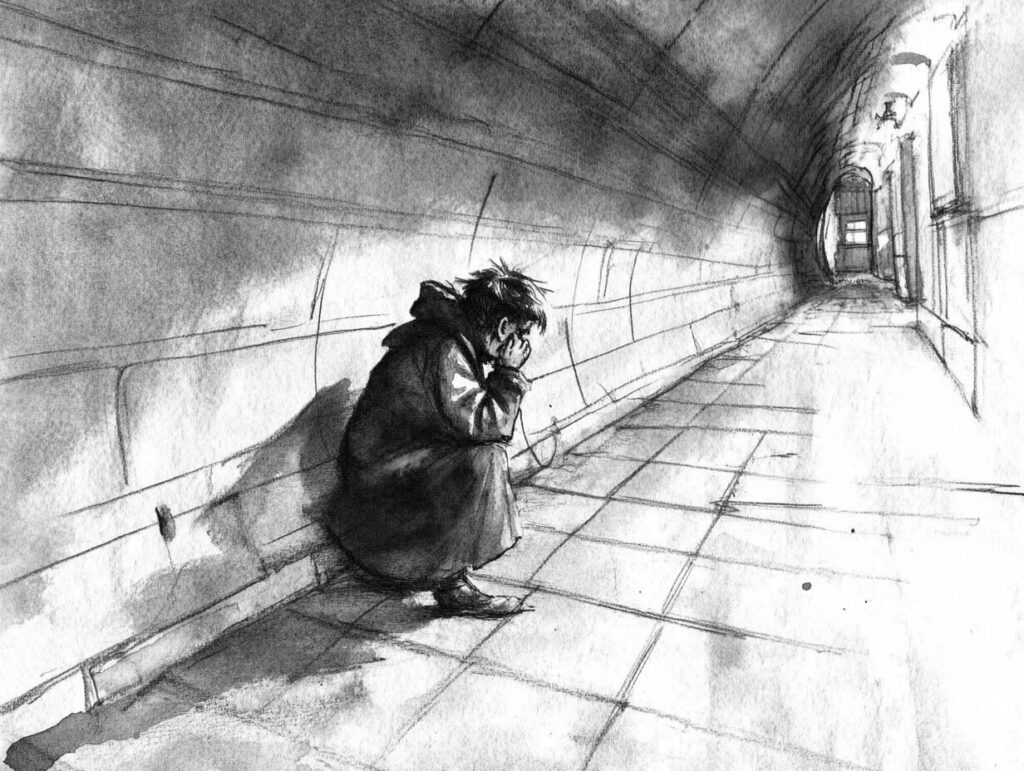

The unnamed narrator of “Notes From Underground” is a man (widely referred to as “Underground Man“) who is so neurotic that he can’t do . . . anything. He can’t really work, he can’t form relationships, he can’t communicate with anyone. He tries, but he overthinks every aspect of every relationship and ultimately screws it up. All that’s left for him to do is live (literally) underground and isolate himself from everyone and everything.

I Think You Ought to Know I’m Feeling Very Depressed

In the first half of the novella, Underground Man talks directly to his readers about what is wrong with him and what is wrong with the world, but readers will agree with almost none of his observations — nearly every statement he makes is contradicted by another. At one moment, he calls himself “wicked,” and in the next he is “noble.” He hates love and loves hate, resents everything but blames himself, and cannot seem to stick with any decision he makes without second-guessing.

This is where the song lyrics I mentioned earlier started to go through my mind in a loop — Underground Man isn’t actually talking to anyone. He’s talking to himself. The “gentlemen” he continually addresses, as if the book were written for someone, don’t exist — the book itself is part of his downward spiral.

We all imagine conversations. You think about what you’d like to say to your boss, or what you’d tell the guy who just cut you off on your way to Chick-Fil-A, or how you’d win over that girl at work you’ve had a crush on for six months. In your own head, you’re a hero, you’re noble, you know just what to say.

Of course, we never say those things. Or, at least, we rarely do. And we very often feel guilty about not being able to be the person we think we ought to be, the person we imagine we are.

Underground Man takes that self-talk to an absolute extreme — it is the only kind of talking he does. The whole book is him speaking to himself in this way.

He thinks about what he’d like to say, what he’d like to do, he realizes he can never do or say those things, and then he beats himself up for his cowardice.

I Resent the Implication

The second half of the novella sees the Underground Man discussing some of the things that have gone wrong in his life. It’s basically him mucking up relationships with old schoolmates and then hollering at a prostitute one night when he’s really drunk.

It’s clear that, while he blames himself for his wickedness, he also resents everyone else for not being as messed up as he is. Can’t anyone see? Doesn’t anyone realize how terrible it all is? Of course they don’t; they’re all fools. But if only he could connect with them, then maybe he’d be able to turn his life around.

He is very nearly able to make some kind of “real” connection with the prostitute (Liza) that he hollered at, but he ruins it, of course, by vacillating between wanting to “save” her and calling her a fool for thinking she can be saved.

Underground Man ultimately breaks down briefly and hits upon one of the truest moments in his entire existence when he says, crying,

“They won’t let me . . . I can’t be . . . good!”

It’s All Good

If you’ve never felt that way, then existentialist literature might not be your bag. Odds are, though, that you can sympathize at least a little with Underground Man. Like it or not, most of us search for meaning in life. We want there to be an answer, and for a lot of us that answer is that we want to be “good” people.

But what if you were never able to figure out what it meant to be “good?” What if that meaning eluded you, or if you felt like you could never achieve it because society wouldn’t let you?

There aren’t a lot of books on this list from which I can glean some kind of practical moral, but “Notes From Underground” does provide some semblance of a lesson: Don’t talk to yourself the way Underground Man does.

Modern psychology calls this negative self-talk and its characteristics are a list of issues that the narrator faces: catastrophizing, mind-reading (supposing the thoughts of others), blaming yourself for things outside your control, and approaching life as an all-or-nothing event.

I’m certainly guilty of all of these things, and reading Notes puts a lot of those thought processes into sharp relief. So, even if you find the Underground Man to be utterly reprehensible and you struggle to finish the book because he’s just so thoroughly dislikeable, there’s still value to be found.

Psychopathy

Misleading me over and over

Psychopathy

Misleading me over and over and over

Don’t you dare point that at me

* * *

Here’s a biography of Fyodor Dostoevsky from Britannica.

“Notes From Underground” on Goodreads.

Here’s that Tool song (Culling Voices):

(Watch out: It’s over 10 minutes long. (Insufferable.))