The Old Boy informs me that I spend too much time talking about school, and that when I talk about school I sound like I’m complaining. “Nobody will read that because nobody wants to hear teachers whinge,” his notes said. “That’s the entire basis of America’s education system.”

I wish they’d never showed him how to send text messages, but he has a point. School is insidious; it seeps into too many aspects of my daily life and I shouldn’t let it.

Anywho. Let’s talk about the Silk Road.

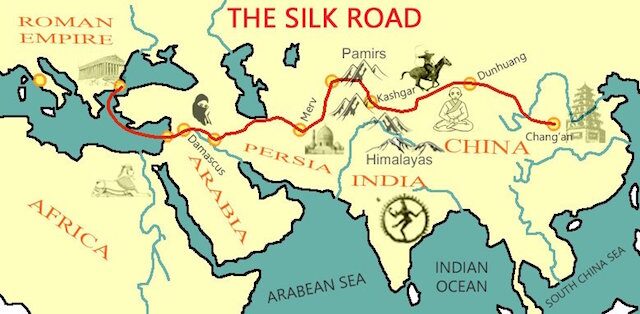

Pictured above, the Silk Road is one of the most famous trade routes ever and has been utilized in one form or another for several centuries. Connecting Europe with the Middle East and Asia, you can tell by looking that the Silk Road goes through all sorts of fun places where you aren’t at all likely to get kidnapped or murdered. The Silk Road is also well known for passing through areas of tremendous political stability where there are hardly any wars at all and everyone gets along pretty well. It is such a chill part of the world that most travelers choose to go down the Silk Road on recumbent bikes, their only real complaint that they wished there were more lemonade stands along the way.

In all seriousness, before sea routes became more practical, the Silk Road was one of the only ways to spread wealth and culture between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. It may not be safe, but it is an exciting road that connected a whole slew of ancient empires. If you were a trader or a merchant, this is where the action was.

In the year 1271, a guy named Marco Polo traveled down the Silk Road causing a ruckus and making all sorts of new pals, and news of his exploits were one of the things that sparked a tremendous European interest in the dealings of China.

If this sounds familiar, it should. We all studied it in 6th grade (but forgot most of it by 9th).

Anywho. In the 1980s, after a couple hundred years of the Silk Road being impassable due to wars and closed borders and stuff, a Scottish historian and traveler named William Dalrymple realized that, with the right visas and a little planning, it might be possible to travel the whole lengthy of the Silk Road again. He decided to give it a try, and this book is the result:

It’s pretty good so far. I do worry that it’s going to pan out to be something spiritual, that the author is going to somehow channel Marco Polo or something and experience a profound awakening by sleeping in the same ditch where Polo once relieved himself.

I don’t think there’s anything fundamentally spiritual about traveling, and it bugs me when travel writrts pretend there is. Can it be spiritual? Sure, but I tend to think of it on an (auto)mechanical level. You can think of yourself as a Datsun pick-up truck, and your spirit as, perhaps, a carburetor. If you travel around long enough, you’re eventually going to realize that your carburetor needs replacing. Same for the tires and the windshield wipers and the oil and eventually the whole transmission’ll needs work. It doesn’t matter where you are when it happens; all that you need in order to make these realizations is to keep moving.

Traveling changes you no matter where you go. You learn empathy, you learn patience, you learn humility. (All very, very spiritual.) But you could be driving across Alaska when you learn these things, or on a boat in Indonesia, or hanging out on a beach in Brazil.

My point is that following the path of Marco Polo might seem cool, but there’s nothing inherently better about it than any other road you may travel. The author certainly will garner no better understanding of the actual Marco Polo than he would if he were swimming through the canals of Venice playing a game of Marco Polo with the citizenry.

Still, it was probably a wild trip and I’m excited to hear about it.