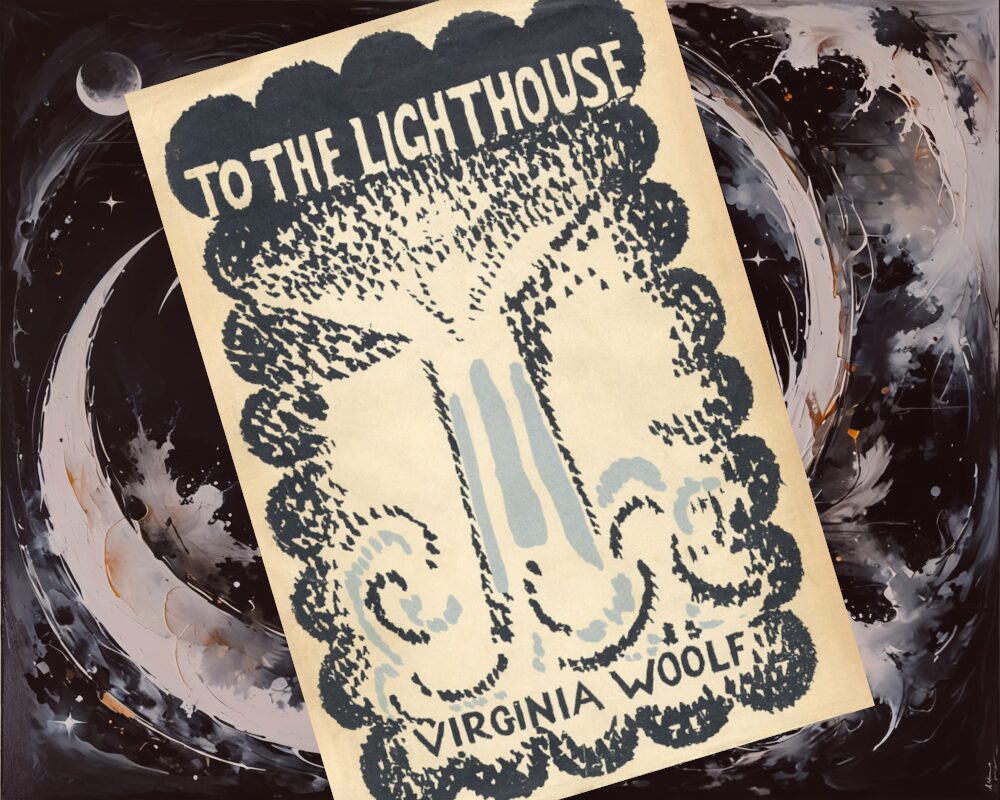

After reading “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” I thought it would be FUN to read a little bit of the beast herself. So, I took a trip to a used bookstore and found a copy of “To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf which is #987 on the list of Books to Read Before You Die.

It was cheap.

By “cheap” I mean the bookstore paid me to take it. They seemed happy to see it go. “Finally,” the cashier mumbled, reaching into her pocket and tossing a pinch of confetti onto the counter by way of celebration.

Since finishing the book, I’ve been struggling to figure out a way to talk about it in a positive way. I don’t think I’ve landed on the perfect “format” for a blog like this, but one thing I don’t want is for this to be the sort of thing that rips books apart for their perceived failings. I’d rather it be something that focuses on the positive. A “Ted Lasso” sort of book blog, even if I constantly struggle to maintain that positivity.

Let Me Think About It

Honestly, though, I did not enjoy “To the Lighthouse.” Reading it was more work than my actual job, and I kept losing the thread and having to back up a page or so to reread parts. Was I distracted by how stressed I am due to work and personal stuff? Sure. But, based on what I’ve read, I’m not alone in finding my mind wandering when reading Virginia Woolf.

The issue is that Woolf is a Modernist author who is most famous for exploring “stream of consciousness” writing. Born in London in 1882, Woolf was raised in a wealthy family and began writing at the age of 18. Her first book was published in 1915 and she continued writing nearly until her death in 1941. “To the Lighthouse” was published in 1927 and examined one large family’s attempt to … visit a nearby lighthouse?

That’s actually the plot?

Anyways. This part of thee early 20th century was Prime Time for Modernists, who reacted to the literary establishment by testing out new forms and narrative styles. A whole slew of young authors seemed to collectively rise up and shout, “F you, Dickens! We’ll do was we damned well please!” I’m sure it didn’t hurt matters that Woolf was wealthy enough to start her own publishing company, Hogarth Press.

Essentially, Woolf wanted to try new things, so she got all caught up in trying to write in a way that captured the inner workings of her characters. I heard that she used to sit around and think about thinking — metacognitive reflection — and would use that in her writing.

Marcel Proust probably did the same thing, but he did it in bed while thinking about his mom.

You Got Psyched Out

Was Woolf taking an important step in the development of modern literature? Absolutely. In a sense, “stream of consciousness” is an attempt to marry literature and psychology. Woolf literally tried to get into the heads of her characters, embracing the difficulty of it and the way thoughts seem to form as if out of thin air, inexplicable and confounding.

There are two problems with this, in my opinion.

First, you can’t ever accurately capture a person’s thoughts. (I’m secretly solipsistic, it turns out.) Virginia Woolf didn’t know that, of course, and it shouldn’t have stopped her from trying, but the fact of the matter is that our experiences are our own and understanding — truly understanding — the perspective of another person is nearly impossible.

What we’re getting in Lighthouse is how Virginia Woolf thinks people think, and that is represented in the printed word, which doesn’t ever accurately portray its subject matter. It’s a fallacy within a fallacy, a wheel within a wheel.

The second problem with stream of consciousness is that it’s just bad writing.

Before you get up in arms at my disparaging a literary titan, let me explain what I mean; stream of consciousness is often riddled with run-on sentences. It’s one nonsensical aspect of trying to capture “consciousness” that a lot of Modernists fall into.

Check out this monstrosity:

“Also the sea tosses itself and breaks itself, and should any sleeper fancying that he might find on the beach an answer to his doubts, a sharer of his solitude, throw off his bedclothes and go down by himself to walk on the sand, no image with semblance of serving and divine promptitude comes readily to hand bringing the night to order and making the world reflect the compass of the soul.”

I just typed all that and I still feel like I’m not understanding the thought process that’s going on. I mean, if you get it, great. Maybe it resonates with some people. But it’s work to read, and literary diarrhea like that is half the reason I lean towards minimalism.

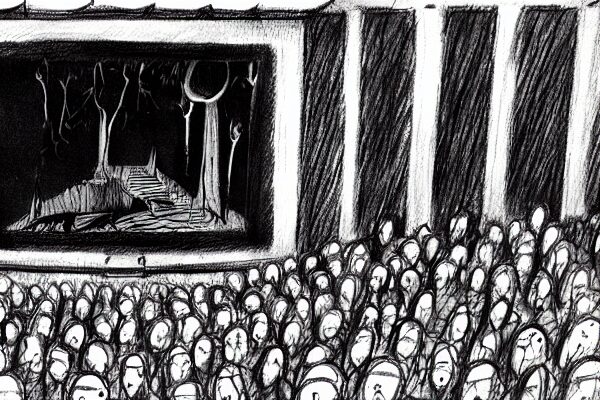

It reminds me of the parable of the avant-garde violinist.

Once Upon A Time…

…there was a violinist whose skill and knowledge of the violin surpassed all others. He lived and breathed his instrument; when he slept, he kept it clutched to his chest; when he ate, he wiped crumbs off its lacquered surface; even when he bathed, the violin was not far from his reach.

Nobody, the violinist figured, had ever truly explored the sounds of which his instrument was capable. So, he began composing.

Typical music notation was of no use to him — the violin, he knew, could play notes between the notes — and the blazing speed and languid slowness of which it was capable could not be expressed on paper. No pen could write the sound of his nails scratching the wood or the creaking of the violin’s neck as it was brought close to snapping. You could not write the sound of a pen knife slowly cutting through the strings. No; his compositions could only ever exist in his mind, and there they burned.

The songs he composed tested the limits of not only music theory but the tensile strengths of wood and gut. He played notes higher than any you’d ever heard, and notes so low that fog horns grew envious. He played notes that droned on and on for weeks, and some notes that were over so quickly you weren’t sure if you’d heard anything at all. He tapped on the violin’s back with a hammer and slapped the instrument into shallow water, creating sounds no one had ever dreamt of.

One evening, he put on a concert that was to be the grandest performance of the violin ever to grace a stage. In the audience were countless celebrities & politicians, along with world-famous musicians & composers. Bach was there, along with Chopin, and Beethoven too. Impossible! you say?That’s just how unique this violinist was.

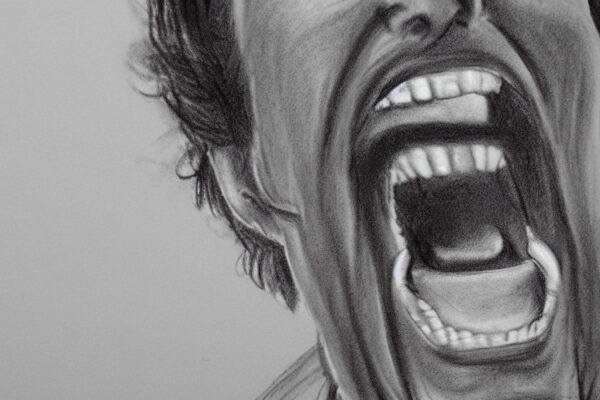

The violinist soared that night. He leapt and he twirled and from the violin issued an unimaginable cacophony. When he was finished, he was covered in sweat, tears, and not just a little blood. The violin lay in ruin at his feet like the body of a conquered enemy.

And when the last note echoed through the concert hall and out across the open sea, nobody clapped. Nobody cheered and nobody cried “Bravo!”

Because, as technically masterful as it might have been, in the end it was just two hours violent noise that nobody could understand.

The point, of course, is that the avant-garde might be appreciated by some, but even if you’re the absolute BEST at what you do, the end result might not be appreciated.

Did Virginia Woolf achieve something by trying to get into the heads of her characters using stream of consciousness? Sure she did, but to a lot of us it sounds like a madman whacking a violin with a hammer while mumbling, “Listen to how unique it sounds!”

When sometimes all you want is a song you can dance to.